Demonstrating “bounded habitats of knowledge” using sudoku problem measured by N2pc signal.

05 Nov 2023

This study aims to demonstrate “bounded habitats of knowledge” (MacLeod, 2018). My previously registered study tests whether asymmetry retrieval of semantic and episodic memory in problem-solving tasks can be modelled using ACT-R. It allows for a more realistic model of human problem-solving cognition thus it tells us the problem-solving process, including memory retrieval. In the process of retrieving heuristics, the model (Wang et al., 2009) uses the ideal valid information to make the most uncomplicated problem-solving process. Assuming this valid information, they created a model so that irrelevant information is not recalled because “human being always attends and selects useful information actively in heuristic strategy (Wang et al., 2009).”

However, “bounded habitats of knowledge” tell us that the “useful” information varies depending on the subject of the problem-solving task – e.g. different researchers have different ways to approach the same question. To experimentally create a situation where the usefulness of information is in a controlled manner, the current study uses two types of tactics to solve the sudoku problem proposed by Lee et al. (n.d.). One is the Cell-based Tactic (CbT). A subject is designated a specific cell in the sudoku grid, where a specific number has to be determined by the subject. The other tactic is the Number-based Tactic (NbT). A subject is given a number and has to find a cell to hold the digit.

The reason for using those tactics is that they differ in the approach to get the identical outcome of the sudoku puzzle hence it is analogous to the concept of “bounded habitats of knowledge”. CbT requires a subject to look through a relevant row, column, and box of the grid so that already existing numbers can be excluded. Then the remaining number becomes the answer to be placed in the cell. Using NbT, a subject looks for the same number as one that is given so that a subject can avoid choosing a cell that is not supposed to have the number. Thus the difference between CbT and NbT is whether a subject looks through multiple numbers of digits in the grid or only focuses on one number of digits.

To quantitatively measure the difference in those tactics, this study uses N2pc signal (Luck & Hillyard, 1994). Mazza et al. (2009) reported that the magnitude of N2pc increases as a subject attempts to enhance recognition of the target stimulus. In the current study, this enhancement is considered to be made by NbT because it only focuses on the same number of digits among the other distractors. Thus greater magnitude of N2pc is thought to demonstrate the “bounded habitats of knowledge” in different tactics to solve the sudoku problem. Therefore, I hypothesise that the magnitude of N2pc is greater when a subject uses NbT to solve a sudoku problem than when using CbT.

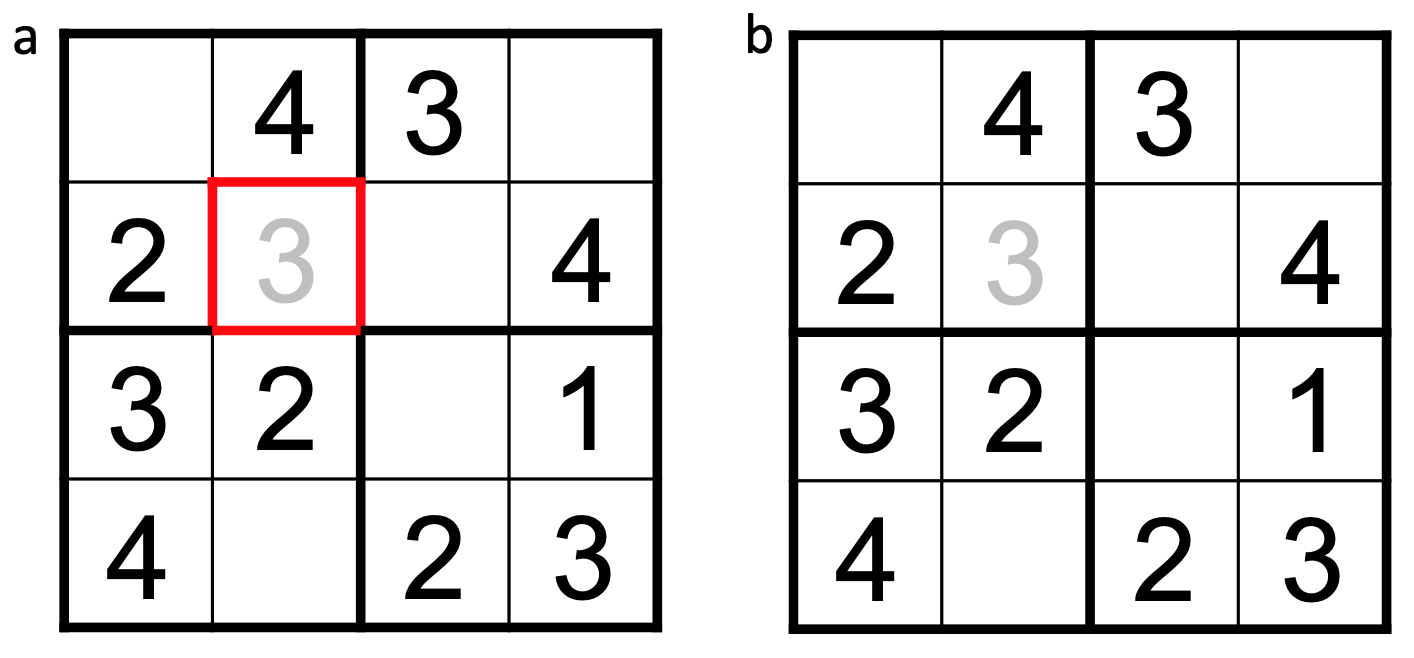

Methods: In this study, 30 participants are recruited of which demographic information will be collected. They are told how to use two tactics (NbT and CbT) to solve the sudoku problem before the experiment. The experiment procedure is the same as the previously registered report, including only the sudoku part. A red fixation cross will be presented for 2 seconds (s) followed by a sudoku problem displayed until a response or 20 s at maximum. (An example of each problem type is shown in Figure 1.) Then, a blank grid will be shown for 2 s followed by 2 s feedback. Between each trial, a white fixation will be presented for 10 s to rest. A participant completes ten practice trials and sixty trials of which half is trials using NbT and the other half is using CbT. Trials with different tactics are randomly presented.

I use an Emotiv EPOC X-14 Channel Wireless EEG Headset to collect the data. The collected data will be processed using MatLab by applying high and low pass filtering, artifacts removal by FieldTrip (Oostenveld et al., 2011), baseline correction, and each epoch will be cut 100 ms prior to and 600 ms after the onset of the sudoku problem displayed. Then, data analysis will be done by conducting ANOVA on N2pc peak amplitude values (Mazza et al., 2009).

Figure 1. a is an example of sudoku problem in the Cell-based Tactic, b is an example of sudoku problem in the Number-based Tactic. A grey digit “3” is the answer to each problem, which is hidden in the actual experiment.

Reference:

Lee, N. Y. L., Goodwin, G. P., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (n.d.). The psychological puzzle of Sudoku.

Luck, S. J., & Hillyard, S. A. (1994). Electrophysiological correlates of feature analysis during visual search. Psychophysiology, 31(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02218.x

MacLeod, M. (2018). What makes interdisciplinarity difficult? Some consequences of domain specificity in interdisciplinary practice. Synthese, 195(2), 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1236-4

Mazza, V., Turatto, M., & Caramazza, A. (2009). Attention selection, distractor suppression and N2pc. Cortex, 45(7), 879–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2008.10.009

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E., & Schoffelen, J.-M. (2011). FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2011, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/156869

Wang, R., Xiang, J., Zhou, H., Qin, Y., & Zhong, N. (2009). Simulating Human Heuristic Problem Solving: A Study by Combining ACT-R and fMRI Brain Image. In N. Zhong, K. Li, S. Lu, & L. Chen (Eds.), Brain Informatics (Vol. 5819, pp. 53–62). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-04954-5_16